Time to go mobile, part 2

The talent-versus-luck simulations again. I started exploring what happens if the agents move before Christmas, but I've only now had the chance to test it systematically.

To very briefly recap, the original claim was that since abilities allegedly follow a Gaussian distribution (hint : there's little or no evidence of that but oh well) and wealth follows a power law, this might indicate that luck plays a major role in acquiring wealth. Simulations showed this could work.

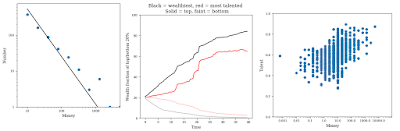

Previously I showed that this was because the effects of talent were horribly restricted, only affecting the chance for an agent to exploit a lucky event. If talent is allowed to also change whether agents avoid unlucky events and the original luck status of the events, then the same power law of wealth arises while showing a clear wealth-talent correlation.

So here (after much tweaking and fine-tuning) I've altered the distribution of events and allowed the agents to move. The events now start such that at the far left of the world they're all unlucky and at the far right they're all lucky, with a linear interpolation in between. The agents move randomly by default. However, there's also a chance that they will move directly left or right, i.e. towards regions dominated by good or bad events. This chance is set proportionally to their talent, such that the most talented agents always move directly right whereas the stupidest agents always move directly left. Agents of perfectly average ability always move randomly, with a linear interpolation between those extreme cases. Although fine-tuned, it basically works. The resulting society is highly meritocratic, with the wealth of the most talented closely following that of the richest agents, a clear talent-wealth correlation, and a very similar wealth distribution as in the original case. More details in the main document (link should go directly to the new section) :

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1TD1PCW1IG2BlBQ27GPe5Nqi5phjg4qXwhpgEfJAgbBw/edit#heading=h.g5576cfgvsjy

I think this is probably a good point to stop. It's very important to realise that these models are only analogous to reality : they are not direct simulations. Of course in reality people both influence the events they experience and are subject to much more complex geographical factors that affect their available opportunities. But there seems more than enough now to give some interesting interpretations that challenge the original findings. I'd like to try and publish this and move on to a different hobby.

... I have enjoyed this series immensely. All the old adages about Luck favouring the Prepared and suchlike are borne out in many of your models.

ReplyDeleteFor all the caveats you might issue about how these models are only analogous to reality - we might ask in our turn how "reality" works. Good old Plato says all we'll ever say is only imitation and representation.

When black people in the United States turn, enraged, upon a society which has demonstrably jiggered the odds against them as surely as any pair of loaded dice, screaming "Black Lives Matter" - the white society gazes upon them and dispassionately responds: "All lives matter." - despite the inescapable facts of the matter.

Until fairly recently, Sociology as a discipline has never been obliged to resort to statistics for many of its conclusions. Were it to do so, it might be taken more seriously.

For my part I've found the ambiguous nature of the models more interesting than direct, literal simulations. A literal recreation can only be right or wrong. A more analogous model forces the question as to which conditions it applies. From what I've read of other agent-based models, they're at a similar sort of state : they can't recreate real-world situations yet, they are certainly nowhere near falsifiable in the classical sense, but they can offer insight into what might be happening. Asimov's psychohistory is a long way off, but using models to try and understand what's occurring (rather than yet predicting what will happen next) is still valuable in itself.

ReplyDeleteI had great difficulty even explaining the original paper to my mum (a sociology teacher). As soon as she understood what it was doing she looked aghast that anyone would contemplate something so obviously nonsensical. And it is, if you take it literally. But I think if you deal with it on its own terms then it raises interesting questions in a new way : what do we really mean by talent and luck, how much inequality should a meritocracy have, how can we decide if talents are being used properly, etc.

There are events that aren't much susceptible to luck like cancer, but having resources would allow you to shed most of the ill effects of a dose of bad luck. Any interest in adding that wrinkle to the model?

ReplyDeleteAlan Peery That's sort of already included, especially here : https://docs.google.com/document/d/1TD1PCW1IG2BlBQ27GPe5Nqi5phjg4qXwhpgEfJAgbBw/edit#heading=h.oa3a1zrn8fhn

ReplyDeleteIt's not something I've checked too much, but what I found was that in general the rich always get richer - but this is a selection effect rather than a causal relation. As well as the wealth fraction, I also plot the absolute wealth evolution of the richest/most talented etc. at the end of the simulation. To be among the wealthiest, it turns out, usually requires a steady increase of wealth throughout the whole run (there are some exceptions of course but that's the general case). Once an agent is one of the wealthiest after a typical 80 timestep run, they tend to be so wealthy that they endure completely different conditions just fine for another 80 timesteps - even if that means encountering more bad luck than they did previously.

A caveat is that I only tested this for the standard random distribution of events/agents. It would certainly be possible to break this with enough effort, e.g. if the wealthiest start to experience continuous bad luck then they will eventually slide into poverty. I'm also not sure if I've plotted the wealth of the right agents in the event of resetting their positions, so I'll check that.